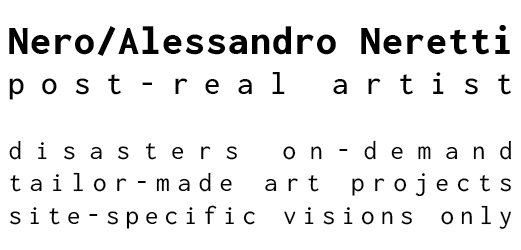

Life is a burning tire

Museum Beelden aan Zee

The Hague/NL

2017

[FIRST HALLWAY]

THE END IS NEAR, 2017 | multilayer pine wood, iron | 59,5 x 39, 5 x 33,5 cm

‘WARNING! The end is literally near, much nearer than you’d think. Time goes by and the end is just around the corner!’

column barefoot, 2017 | glazed earthenware, worn-out car tires | 129 x 69 x 73,5 cm

‘Very often construction does not take into account the right proportions in relation to historical bases and every so often these bases are the bare feet of grotesque animals.’

(L) series one bicycle wheel: new world fucker, 2017 | (R) series one bicycle wheel: life is a burning tire, 2017

series one bicycle wheel: new world fucker, 2017 | glazed earthenware, worn-out bicycle tires, aluminium, iron, rubber | ø70,5 x 8,5 cm

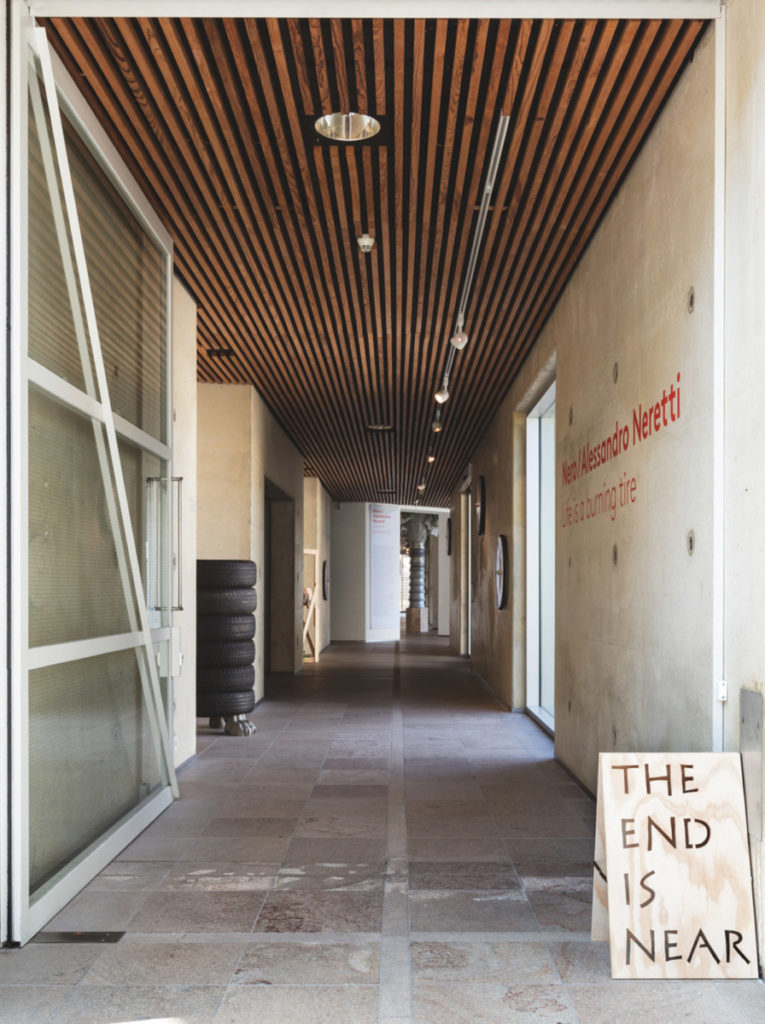

series one bicycle wheel: we go for disaster, 2017 | glazed earthenware, worn-out bicycle tires, aluminium, iron, rubber | ø71 x 9 cm

‘Life on occasion invites us to throw out all certainties to launch ourselves on a new journey. It takes courage and we should be proud of our choices even if they turn out to be a colossal disaster for some.’

WALL STREET JOURNAL, Friday Sunday, February 24-26, 2017 > FINANCIAL TIMES, Friday 12 May 2017, 2017

salvaged papier-mâché sculpture from mid nineteenth century, salvaged wood, glue, iron, paint, aluminium hand truck, mixed media | 166 x 89 x 62 cm

‘Recovered from the cellar where it had been abandoned and restored to new life. In the same way faith returns and is carefully protected, carrying it through time.’

//////////

Historical note:

Born in 1568, the young Luigi (or Aloysius) Gonzaga is portrayed wearing the black and white novice’s surplice, stamping on the crown, symbolically distancing himself from the title of nobility and the rights to his inheritance. He is only ten years old as he takes the oath of chastity and obedience, determining to devote his life to the underprivileged.

Possibly attributable to the Bottega Collina Graziani (ca. 1850).

SCENARIO | PICKLOCK

a conversation between Alberto Zanchetta & Nero/Alessandro Neretti

A: THE END IS NEAR is the declaration written on the sign at the beginning of the exhibition. All one has to understand is whether it means the beginning of the end or the end of the beginning. But let’s proceed by steps. During our last conversation you explained the meaning of post-real (you defined it in an ambivalent way back then: as something that has just been experienced or as the counterfeiting of reality – in other words, an artifice). Since you have continued to develop the said concept through your works, I would be interested in knowing whether this post-real of yours has been subjected to modifications over the past few years. But I would especially be interested in knowing: whatever happened to the pre-real?

N: The task of THE END IS NEAR is to mark the beginning of the exhibition by drawing an imaginary yet visible line inside the museum premises. It arouses the attention of audiences by foretelling a change and announcing that the spot marks the beginning of a new path. By playing with the sign at the end of the exhibition, namely THE END, one has the perfect sensation of being part of the artist’s pre-established pathway – a narration, a divertissement that only reveals itself at the last minute.

The post-real continues to overwhelm me at every moment, that type of connection or perhaps it would be best to say those clear visions continue to be a part of my way of working. Should my task during this interview be to show my true self, as I always do every day, I cannot hide that your question regarding the pre-real has caught me unawares… the pre-real is nothing else that an acquired knowledge of things that are happening in all of their forms, either material or immaterial… and the first thing that comes to my mind is Gustavo Adolfo Rol. During the preparation of this project, some explicit signs occurred fore-telling the work was going in the right direction, that I was fully experiencing the moment and that I had made the right decisions when choosing the works to be created.

A: The setting of international art offers us the possibility of seeing many installations, but less and less sculptures. But in your case there is a balanced fusion of readymade and handmade. After having confirmed my availability for taking part in this conversation, you must know that I had promised myself that for no reason would I inconvenience Arturo Martini – in fact, I wanted to avoid quoting his essay ‘Scultura lingua morta’ (Sculpture, a dead language) for the umpteenth time. But it is now impossible for me to avoid this reference. The truth is that our cosmopolitan society no longer allows us to be acquainted with one language alone; when one thinks and speaks in many different idioms, some unexpected neologisms eventually rise up. I wonder whether this might also be happening in the field of sculpture.

N: This question obliges me into immediately confronting a series of considerations, although I had in turn promised myself that I would not make out any numbered lists:

1. Have always conceived my productions as site-specific projects that basically eradicate the concept of exhibition as they are open towards comparisons made of spaces, concepts, architecture, contexts, cultures and locations; As I always create new works… this allows me (in addition to quenching all of my strength) to approach my clients in an unexpected way, engaging in dialogues made up of a language in constant evolution. A sort of art/(s)cul(p)ture that is alive and ravenous every step of the way.

2. In my view, Arturo Martini’s essay work expresses the malaise of a lifetime spent in his career since, working for the regime, he was burdened by commissions that gave him economic freedom but did not leave him enough time to look for new languages or ones that were alternative to his own. This condition tied down his research since the restraints to his works were those dictated by strict commissions that did not leave him any space for looking around and glimpsing at the real potential of his sculpting.

3. The famous phrase “art is not interpretation, but transformation” in some way marks a tangible turning-point intrinsic to sculpture; as much as I am a great admirer of Arturo Martini’s work, I cannot help but think of the visual evolution implemented by contemporary sculpture over the past thirty years as being surprising at the very least – and therefore vital.

4. Compared to the neologisms that you are speaking of, in this display I am also presenting a video entitled tales from the northern seas1 that was filmed in the vicinity of the museum, amidst cement, sand dunes and the North Sea.

The video, divided into three chapters, uses as its subjects some of the works on display:

CHAPTER ONE: the treasure narrates the casual discovery of an ancient sculpture [fainted laocoonte after party, 2017]. Filmed in two frames, the first one describes (general, with subject and horizon) the vision of the collective story and then switches to (film shot using a smartphone) a personal vision. Using all the strength he can muster, the subject attempts (in a blend of pathos and awkwardness) to extract the heavy sculpture from the sand and take it with him.

CHAPTER TWO: the travel is inspired by the great sails flying on sea-vessels [series one bicycle wheel and project to be done (sailing)], I made a sail using an old hemp cloth and used it to sail the shoreline at Scheveningen.

In CHAPTER THREE: the end the people walking along the beach interact with the signs boasting THE END and THE END IS NEAR. Screened backwards, the video has the power of absorbing all the actions of the figures and exclusively render the sea with its waves that (incredibly) splash back onto themselves, in a time that is reminiscent (in a poignant and poetic manner) of all those moments that can never come back in time.

The music composed by Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621) has been performed by the BRISK Recorder Quartet Amsterdam and Camerata

Trajectina.

5. “Più vivi di così si muore” (You just can’t get any more alive than this).

A: You’ll agree with me that artists from the last generation favour discarded/recycled material, or poor material to say the least, often and willingly purchased in hardware department stores. Even your works do not escape the ‘do-it-yourself’ sector, to the point of seeming works in progress. Behind their destitute and almost derelict charm there actually lies a hidden wise – as much as savvy – familiarity, the same that can be found in artist workshops with improvised canopies, works arranged on fictitious foundations, objects assembled out of pure pleasure and curiosity. Should I use just one adjective to describe your work, I would not hesitate in the least in using ‘sprezzatura’ (a certain nonchalance) as the word that describes it best.

N: During my gradual approach towards the creation of artworks [1997/1999], I immediately realized that pre-existing material (discards) that had already completed an independent life of their own, could help me in narrating a story … the secret lessons offered to viewers by inanimate material are extremely useful.

For a while now, foundations are a fundamental part of my works. They are the result of some healthy anthropological research contaminated by continuous visions of my real life (post-real). They are launching-pads that begin with sculpture and not simply furnishings used to fill out empty spaces; there is always a close dialogue with the work, in a constant conflict between the ‘contents’ of the sculpture and the ‘perception’ of the backing that implies continuous confrontations made up of misunderstandings and agreements… I love it when a sculpture is nothing without its foundation… this fosters high tension between the elements of the work itself and enables observers to perceive the said tension.

In this project, as never before, we can observe the use of industrially produced elements, as in actually with no title [2016] – the first work created for the museum. I had imagined this piece three years earlier, but since I did not have the elements needed to compose it and since I did not have a project that could be used to contextualize it, it just stayed filed away in my notes.

I’m using this work as an example because I have always employed very complex titles that provide viewers with various meanings linked to the work, establishing an umpteenth operation of sharing with the observer, placing him at the focus of the artist’s thoughts and in the totality of the work itself.

This title is an insult to the series of ‘untitled’ works that infest books and exhibitions, making one believe that the artist has no intention of declaring, affirming, sharing – which reveals profound insecurity and uncertainty, obliging the spectator to perceive what the artwork is and what it wishes to communicate.

On the contrary, this ‘actually with no title’ in some way renders the great uncertainty of the work, which is based upon an unstable balance: two ancient dogs with different weights and measures, balanced precariously on a wooden plank, are playing as if they were on a swing. The clear symbolism of a change that might occur at any time portrays the sense of instability intrinsic to the work.

Sprezzatura (a certain nonchalance) is undoubtedly the word that, referring to my works, best describes them at present.

I have realized, over the course of time, that following the planning and great efforts involved in the production stage, when I observe my works I experience the final result in an extremely superficial manner; I recognize its quality, but condescendingly, as if to completely tune down the work involved. All of this derives from the fact that my mind constantly projects me towards the next objective, waiting to give myself entirely up to the establishment of a new project.

A: Before dealing with the works one at a time, I would like for us to analyze them as a whole. In fact in these works – as you yourself have admitted – we witness a sort of ‘balancing exercise’. Nearly all of them are ephemeral and random structures. The first time we met, you referred having conceived this exhibition as a personal-social [self]portrait focused on insecurity and uncertainty. May we speak of an ‘unbalancing’ exhibition where we witness the collapse of culture, the decline of civilization and the destruction of humanity?

N: Assuming that through his work the artist often speaks about himself, the title of the exhibition life is a burning tire hit me, like all the titles, like a sort of message from the subconscious.

I believe that this is, to date, my greatest personal project for its quality, number and dimensions of the works on display; all of this has channelled into me a series of tensions that, step-by-step, I’ve attempted to incorporate into the works themselves. Continuous setbacks in the production stage have modified pre-established logistics, complicating the path in an unexpected way…

Now I wish to mention some of the excerpts drawn from conversations with Alessandra Laitempergher, which she had printed on one of the exhibition walls:

“Throughout my investigation, I’ve always perceived the intrinsic fragility of everything. My art is a desperate attempt to contain the incredible force humanity is using, trying to dissolve his own past, his own world. This research is burning me down, leaving me used up like a tire in a dump”.

These words sum up my human condition and contextualize my mood within a determined path. We (the world) are gaining access into a period where we will be asked to make decisions that will change the course of the future of our planet. The sooner we become aware of this, the better we will be able to distinguish what is sensibly right to protect and what, on the contrary, must be abandoned.

A: More than the aesthetic value, you often hint at the economic value of a work of art. In this situation, you also insist upon the safeguarding of artistic and spiritual legacies (the two things even seem to coincide). I am referring to the statue of the holy martyr whose ordeals never seem to come to an end. You’ve attempted to restore it – which means restoring its shape and returning its meaning – and preserve it inside a (protective) cell that is simultaneously a transportation crate and a tabernacle for liturgical processions. We wouldn’t be at all surprised if the words HANDLE WITH CARE were written on the outside, not only referring to the sculpture but also to the intended theme – namely religious cults. We are constantly tormented by doubts and, more than anything else, by anxiety for the new. The statue of this saint, which you have saved, risks being subjected to new rites (consumer ones); it is the same lesson instilled into us by most contemporary design, conceived and planned ‘not to last’. Tastes, likewise to convictions, change very quickly; and that’s the reason why we can no longer rely on anything, everything seems destined to semantic emptying.

N: It has by now been established that I tend to insert into each one of my personal projects – like a sort of votive offering – a work that is capable of dealing with the Christian faith not irreverently, but rather with the idea of confrontation so as to foster the establishment of a constructive discussion, an exchange of views between the parties.

Taking one step backwards, while in Christ Child with stigma2 a monkey bearing golden stigma questioned us about the intersection between the creationist dogma (Bible) and the theory of evolution (Darwin), today instead this saint named Aloysius Gonzaga, who had rejected his family’s riches to devote himself to his brethren, is employed as a picklock for a new conversation.

The sculpture I worked on is an old papier-mâché dated 1850 approx. Its title WALL STREET JOURNAL, Friday Sunday, February 24-26, 2017 > FINANCIAL TIMES, Friday 12 May 2017 encompasses the names and dates of newspapers used for its restoration subsequent to its discovery in disastrous conditions. In fact, I used the first newspaper to indicate the date of its discovery (personal event) and the second newspaper to indicate the date in which it was restored to the public (collective event).

I chose these two newspapers of an economic-financial nature because they represent the system rejected by Saint Aloysius and extol his life choices. In a world where processions have been substituted by catwalks and the Nativity scene has been substituted by Santa Claus, this figurative work concentrates its attention on HANDLING WITH CARE its passion, its creed, protected from the wear of consumerism… in constant movement and fearlessly exhibiting it to the world.

A: I have always associated Antonello da Messina’s St. Jerome in His Study with the front cover of Erwin Panofsky’s book entitled ‘Perspective as Symbolic Form’, published in Italy by Feltrinelli (the specific edition dates back to 1987). I derive that you yourself might have cultivated this recollection during your years at the Academy. I still bear in mind that dark green border than ran along the edges of the front cover, with the image of the painting reproduced in the middle, which was in turn bordered in green. To this day, I still remember how the front cover made the architectural geometry of the small study stand out, emphasizing the peculiarity of its ‘palco scenico’ (stage). Instead of limiting yourself to translating it in three dimensions, you gave a new version in a specular and self-moving form, as if intentionally highlighting its artifice and disorientation. Even the few objects present in the painting have disappeared. And now that ‘palco scenic’ (stage) has been emptied out, the scene is no longer occupied by any performing figure. Has that intimate setting, one of research and considerations, lost its function? Or does it allow us to find ourselves wherever we might be?

N: Here I must disagree with you: I do not harbour that same recollection due to the fact that I did not continue my studies at the Academy, but chose a different path after the Art Institute (my choice being greatly swayed by my scarce inclination towards studying, in addition to my limited economic resources).

In this work I’ve attempted to reproduce St. Jerome’s study as I recalled it (studied over and over again during those tedious lessons in Art History), simply using discarded material that I found at the carpenter’s shop. The oil painting by Antonello da Messina had been inspired by the technique used by Flemish artists from the same period. This small painting had been conceived as an actual exercise in style that the author decided to bring along with him to Venice and exhibit it to his future customers.

Proof of concept (ball breaker) was born from my will to trigger continuous action inside the museum; in fact, in the back I applied a photocopy of the original painting, where I wrote TAKE IT! In this way, visitors are stimulated into taking the photocopy and thus making the work an orphan of one of its parts until museum volunteers replace it.

So one clearly goes from a ‘proof of concept’ to a ‘ball breaker’, while keeping the relationship between my past history (memory/painting) and the present (museum/visitors/volunteers) active.

Returning to your question, today I believe there are important problems inherent to reflecting upon something; the individual, through many chances at interconnecting with others, is certainly losing his capacity to find himself outside those infamous social networks. Intimate settings are gradually disappearing to the detriment of a mass vision that is overly broad and therefore risks becoming a non-vision.

A: I am presently looking at the ceramic disks you have framed with some bicycle wheels, which are an explicit tribute to The Netherlands. The decoration draws from the traditional ‘Delft style’, as Wim Delvoye and Marcel Wanders have done a few years before you did. Yet does the nautical iconography that inspired you perhaps conceal a harbinger of doom? What kind of catastrophe are these galleons heading for? Are they perhaps telling us that we are slaves of the past, that we are not capable of living our present, or perhaps that we are deceived by the future? In other words, do we risk being dispossessed of our bodies and our ideas?

N: The most interesting aspect of the series is that the works have been installed on the wall, just like a wheel is fixed to a bicycle. Thanks to a central pin, used in the quick coupling system, the wheel maintains its spinning capacities.

To tell the truth, I do not identify the galleon with a sense of catastrophe; on the contrary, I feel the courage that urged navigators and researchers, who came before us, to leave the mainland towards the unknown. I think this has a very great power; those emotions that pushed them into leaving the certainties of everyday life only to sail to the middle of the sea, across the oceans – I believe this to be the symptom of a strength that cannot be compared to anything else.

I love the spirit of adventure, that curiosity about the unknown that drives you into abandoning the high road in order to travel over untrodden paths, discovering what lies beyond your front door.

Each one of my research periods carries within indelible traces of the artisan and social traditions of the place hosting me… it would have been impossible not to accept the delft-blauw challenge.

Incidentally: Wim Delvoye is a fuckin’ maestro!

A: Alongside the bicycle we find some tyres and wheel rims stacked up in the shape of a pillar. Then we have three motorcycle helmets – one for each hypothetical step of the podium – that you have arranged in the museum plaster casts gallery. In this case, does the concept of attracting attention mean joining the game? In your opinion, is art a sort of competition where the competitors (namely artists and their works) always want to stand out from the rest?

N: I take one step back, only to take one step forwards – I hope.

I personally believe that developing a project is not ‘a game’, but rather the closest one can get to ‘a challenge’.

A challenge with oneself, with architecture, institutions… a contest that leads to the development of the utmost tension between artist and reality. The title of my solo exhibition in 2014 Who is a good boy?3 echoed like a rhetorical question, underlining this constant search for approval on my part. I conducted other activities between 2000 and 2006 (surf, windsurf and snowboard instructor), but for the past 11 years my only ‘occupation’ is being ‘an artist’. As you can well understand, this condition does not allow me any sort of distractions; on the contrary, the challenge of making a living out of this keeps me in perpetual tension. But that same tension implies that I am always on the lookout for people, exhibition areas and collectors to get in touch with in order to work, support my research and (as such) my personal life. It’s like a strange match where – ignoring rules and statistics – you are constantly all in and bet everything you own on yourself and your skills.

A: I agree, it’s best to accept the challenge and take the risk. In summary, I would like to mention the following aphorism: “born an arson and died a firefighter”… Reconsidering the title of your exhibition, I would say that you are destined to die a pyromaniac.

N: Perfect, I go for disaster!

1 As a tribute to Dutch conceptual art (Marinus Boezem, Bas jan Ader, Jan Dibbets and Ger van Elk).

2 Christ Child with stigma, 2014, glazed earthenware, third fire gold, concrete blocks, 143 x 22 x 23 cm.

3 Solo exhibition of the artist staged at MAR – Museo della Città di Ravenna, inaugurated in November 2014.